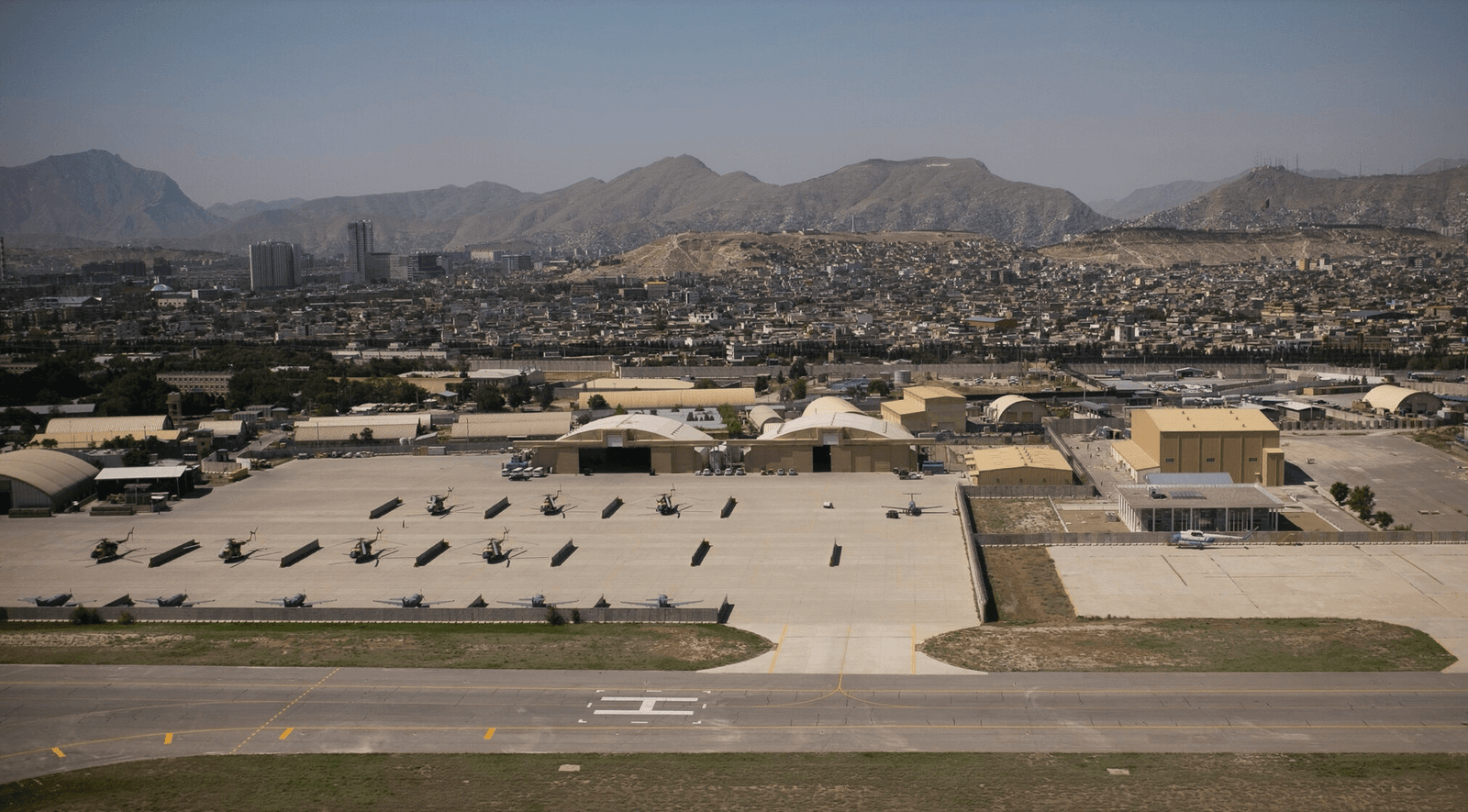

Russian officials have publicly welcomed the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan as a major defeat for the United States. But behind the scenes the Kremlin will struggle to prevent the spread of Talibanism to Central Asia and into Russia itself. It has staged rapid military exercises in Central Asia and along Russia’s borders as a show of strength. And one major way for Moscow to deflect the looming threat is to aim the new Kabul regime against Western interests in the wider Middle East and even globally.

State media and Russian officials have reveled in the sudden and bloody American withdrawal from Afghanistan. The rapid collapse of the Afghan government allegedly demonstrated that the U.S. is a declining global power that cannot be trusted to defend its allies and partners and that NATO is a spent force. Both Russia and China may also test other U.S. commitments in Europe and Asia at a time of acute global uncertainty and the pressure will mount on targeted states such Ukraine, Georgia, and Taiwan.

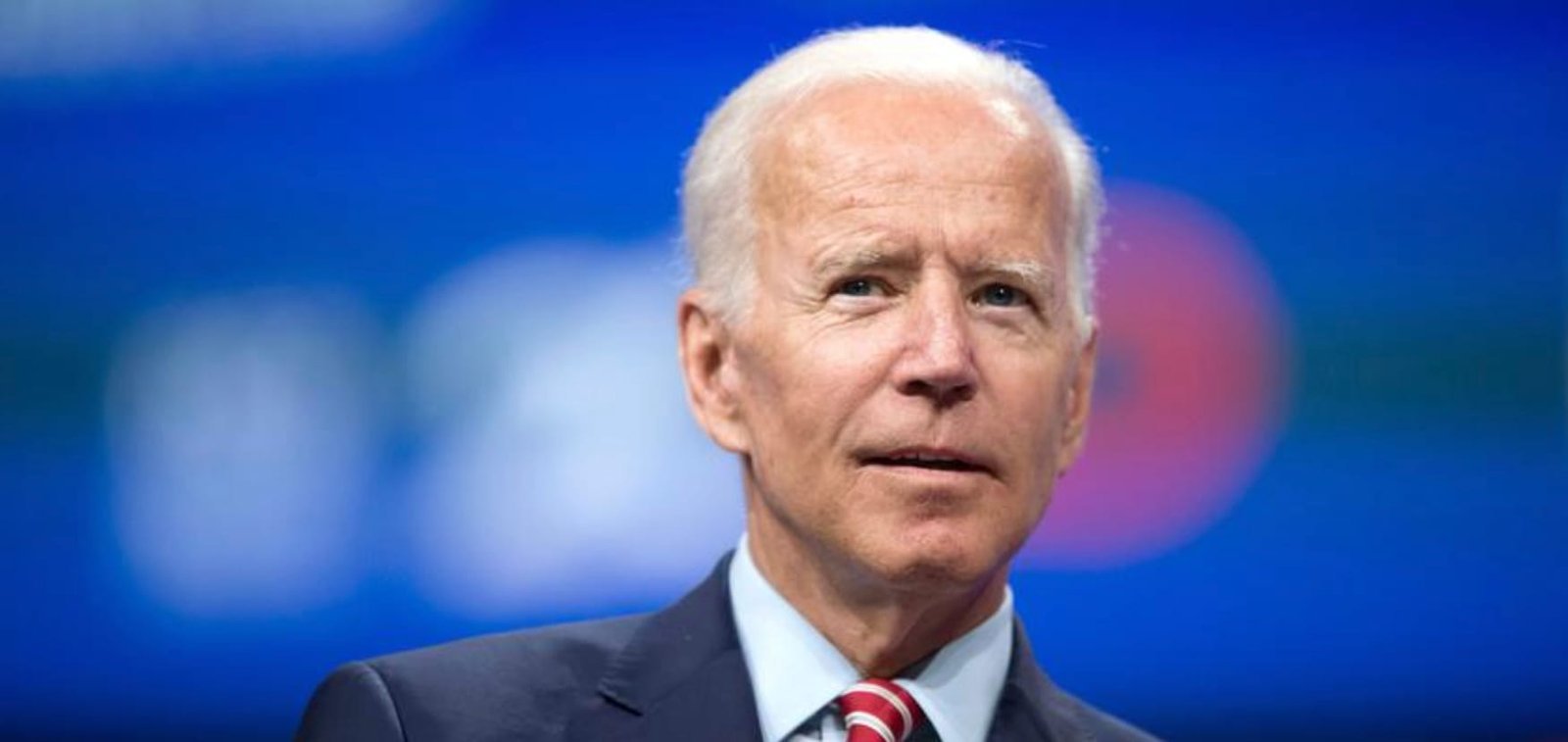

Moscow’s intense propaganda campaign will also be accompanied by moves to steer the Taliban into new anti-Western offensives. The objective is to subvert other Muslim-majority states, spread an authoritarian religious ideology, scale down the American presence, and undermine President Joe Biden’s agenda of democracy-promotion and women’s emancipation.

The more immediate threat to the West and to moderate Islam is a revival of global terrorism. Afghanistan can again be effectively used as a base to recruit, train, and deploy jihadists from different states against Western facilities, allies, and civilians throughout the Muslim world. New attacks on the U.S. homeland and in Europe cannot be discounted and the younger Taliban generation may prove more sophisticated in disinformation campaigns and more capable in cyber war and in deploying bioweapons and other mass casualty devices.

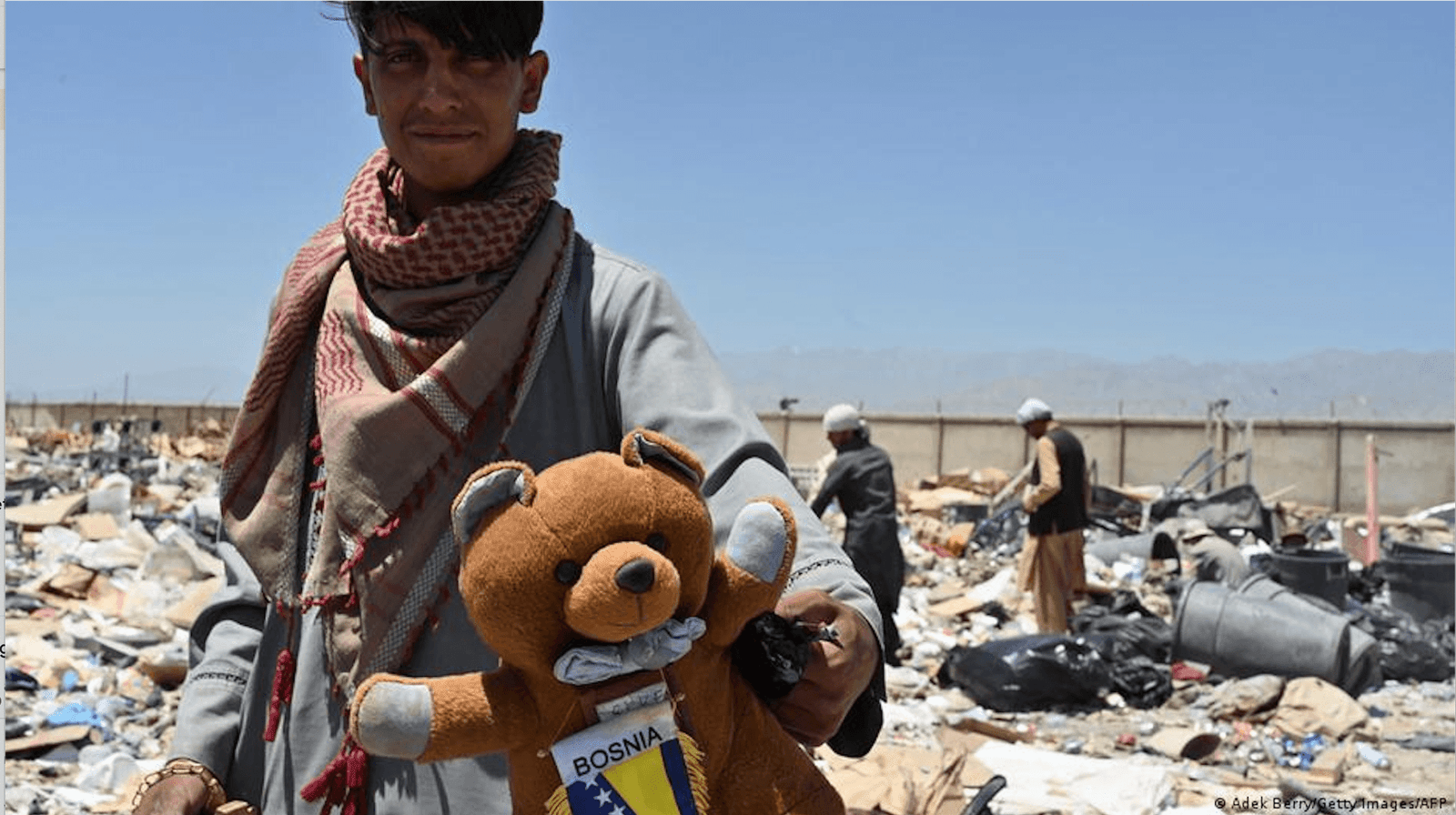

The Biden administration may endeavor to develop ties with the Taliban regime to limit its assaults on the West. There is some hope in Washington that the new leaders in Kabul would be willing to engage in diplomacy in return for a measure of international legitimacy. An alternative option would be to exploit Afghanistan’s ethnic, tribal, and regional divisions to weaken the Caliphate by supporting anti-Taliban forces, particularly those gathered by Ahmad Massoud, son of the legendary anti-Sovietmujahideen commander. Massoud has pledged to resist the Taliban from his stronghold in the Panjshir valley and to recruit experienced combatants.

Moscow has not evacuated its embassy in Kabul after cultivating cordial ties with Taliban leaders over the years and receiving pledges that they will not aim their Islamic revolution against the secular Central Asian states. But the Kremlin’s trust in the Taliban may be misplaced. Moscow’s primary goals in Central Asia are to maintain the region in its sphere of influence, keep the West at a distance, and prevent the infiltration of radical Islamist groups into Russia. It will undoubtedly expand its military presence in the region, including border guards and special forces but this could mean a drawdown of troops in other regions where Russia is already engaged in wars or outright occupation, including Ukraine and Georgia.

Despite the reinforced military presence by Central Asian states along Afghanistan’s northern borders, the regime in Kabul can facilitate the infiltration of various ultra-Islamist groups into neighboring Uzbekistan, Tajikistan, and Turkmenistan and promote radicalization among disaffected locals. A sizeable number of jihadists will also be returning from the war fronts in Afghanistan and the robust heroin trade will help fund insurgency and terrorism.

In trying to block the rise of regional jihadism Beijing is also seeking commitments from the Taliban that it will not assist terrorist groups inside China and will not lend support to the Xinjiang independence movement among Muslim Uyghurs. Beijing will also pursue its economic agenda across Central Asia and will want to entice Afghanistan into its commercial routes across the continent while pushing out American influence throughout the region.

In Russia itself fears are rising about a new upsurge in jihadist militancy and anti-state terrorism, as anger at Moscow’s policies has accelerated during the pandemic and amidst economic decline. The Taliban’s takeover of Afghanistan will inspire Islamist rebel groups in the North Caucasus, the Middle Volga, and other Muslim-majority regions, with many experienced fighters returning home from Afghanistan.

A new round of terrorist attacks in Russian cities can be expected over the coming months, especially if they are supported and funded by the Taliban regime. Afghans have a long memory of the mass murders perpetrated by Moscow during the period of Soviet occupation in the 1980s. The head of the Chechen republic Ramzan Kadyrov has warned of the imminent danger to Russia after the fall of Kabul. He is evidently fearful that his loyalty to President Vladimir Putin may be undermined by a new generation of anti-Moscow Islamists.

A sizeable jihadist movement can reemerge in the North Caucasus and other Muslim areas, aimed at the creation of an Islamist caliphate similar to Afghanistan. In recent days, the arrest of dozens of alleged members of the radical Islamist group Katibat Tawhid wal-Jihad in police raids across Russia indicates growing anxiety in government circles. The special operation was conducted jointly by the FSB, the Interior Ministry, and the National Guard (Rosgvardia) in several far-flung cities including Moscow, Novosibirsk, Yakutsk, and Krasnoyarsk. Those arrested were suspected of promoting terrorist ideology, financing and recruiting activists, and transporting them to war zones.

The ensuing challenges to Russia’s state integrity can also unleash a plethora of ethnic, national, and regional demands throughout the fragile Russian federation. Paradoxically, while Moscow may now view the Taliban victory as a defeat for the West, the U.S. retreat from Afghanistan may have the most destabilizing consequences inside Russia itself.

Janusz Bugajski is a Senior Fellow at the Jamestown Foundation in Washington DC. His recent book, Eurasian Disunion: Russia’s Vulnerable Flanks, is co-authored with Margarita Assenova. His upcoming book is entitled Failed State: Planning for Russia’s Rupture